Giulio Andreotti

| Senatore Giulio Andreotti |

|

|

|

|

59th, 62nd and 71st

Prime Minister of Italy |

|

|---|---|

| In office 17 February 1972 – 7 July 1973 |

|

| President | Giovanni Leone |

| Preceded by | Emilio Colombo |

| Succeeded by | Mariano Rumor |

| In office 29 July 1976 – 4 August 1979 |

|

| President | Giovanni Leone Alessandro Pertini |

| Deputy | Ugo La Malfa |

| Preceded by | Aldo Moro |

| Succeeded by | Francesco Cossiga |

| In office 22 July 1989 – 24 April 1992 |

|

| President | Francesco Cossiga |

| Deputy | Claudio Martelli |

| Preceded by | Ciriaco De Mita |

| Succeeded by | Giuliano Amato |

|

Italian Minister of Foreign Affairs

|

|

| In office August 4, 1983 – July 22, 1989 |

|

| Prime Minister | Bettino Craxi Amintore Fanfani Giovanni Goria Ciriaco de Mita |

| Preceded by | Emilio Colombo |

| Succeeded by | Gianni De Michelis |

|

Italian Minister of Defense

|

|

| In office February 15, 1959 – February 23, 1966 |

|

| Prime Minister | Antonio Segni Fernando Tambroni Amintore Fanfani Giovanni Leone Aldo Moro |

| Preceded by | Antonio Segni |

| Succeeded by | Roberto Tremelloni |

| In office March 14, 1974 – November 23, 1974 |

|

| Prime Minister | Mariano Rumor |

| Preceded by | Mario Tanassi |

| Succeeded by | Arnaldo Forlani |

|

Italian Minister of the Interior

|

|

| In office January 18, 1954 – February 8, 1954 |

|

| Prime Minister | Amintore Fanfani |

| Preceded by | Amintore Fanfani |

| Succeeded by | Mario Scelba |

| In office May 11, 1978 – June 13, 1978 |

|

| Prime Minister | Himself |

| Preceded by | Francesco Cossiga |

| Succeeded by | Virginio Rognoni |

|

|

|

| Incumbent | |

| Assumed office June 19, 1991 |

|

| Constituency | New Constituency |

|

|

|

| Born | January 14, 1919 Rome, Italy |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Political party | Christian Democracy |

| Spouse(s) | Livia Danese |

| Residence | Rome, Italy |

| Alma mater | University of Rome La Sapienza |

| Profession | Politics Journalist |

| Religion | Roman Catholicism |

Giulio Andreotti (born January 14, 1919[1]) is an Italian politician of the now dissolved centrist Christian Democratic party who served as the 59th, 62nd and 71st Prime Minister of Italy from 1972 to 1973, from 1976 to 1979, and from 1989 to 1992. He also served as Minister of the Interior (1954 and 1978), Defense Minister (1959–1966 and 1974) and Foreign Minister (1983–1989), and he has been a Senator for life since 1991. He is also a journalist and author.

He is sometimes called Divo Giulio (from Latin Divus Iulius, "divine Julius", an epithet of Julius Caesar) because of his authority and importance in the history of Italian republican politics. The film Il Divo deals with Andreotti's ties to the Mafia and won the Prix du Jury at the 2008 Cannes Film Festival.

Contents |

Political career

Andreotti was born in Rome[1] and studied law there. During his formative political years, he was tightly connected to the Christian Democratic Leader Alcide De Gasperi. Andreotti has sat in Parliament without interruption since 1946, when he was elected to the Constituent Assembly. He was continuously re-elected to the Chamber of Deputies until President Francesco Cossiga appointed him as Senator for life in 1991.

He was the last Christian Democratic prime minister of Italy, serving from 1989 to 1992. His last term was marred by the revelation of the corruption which ultimately destroyed the party. On October 24, 1990, Giulio Andreotti acknowledged before the Chamber of Deputies the existence of Operazione Gladio, a North Atlantic Treaty Organization secret anti-communist structure. During the first stages of Tangentopoli he was left untouched but in April 1993 he was investigated for having mafia relations. In 1994 the party of which he was a predominant figure vanished from the political sphere.

On April 14, 1986, during his time as Foreign Minister, Andreotti revealed to the Libyan Foreign Minister, Abdel-Rahman Shalgam, that the United States would bomb Libya the next day in retaliation for the Berlin disco terrorist attack which had been tied to Libya.[2] As a result of the "warning" by the supposed U.S. ally Italy, Libya was better prepared for the retaliatory American strike.

Mafia trial

Andreotti was investigated for his role in the 1979 murder of Mino Pecorelli, a journalist who had published allegations that Andreotti had ties to the Mafia and to the kidnapping of Prime Minister of Italy Aldo Moro. A court acquitted him in 1999 after a case that lasted three years, but he was convicted on appeal in November 2002 and sentenced to twenty-four-years imprisonment. The eighty-three-year-old Andreotti was immediately released pending an appeal. On October 30, 2003, an appeals court over-turned the conviction and acquitted Andreotti of the original murder charge. That same year, the court of Palermo acquitted him of ties to the Mafia, but only on grounds of expiration of statutory terms. The court established that Andreotti had indeed had strong ties to the Mafia until 1980, and had used them to further his political career to such an extent as to be considered a component of the Mafia itself.[3]

Andreotti defended himself by saying he took harsh measures against the Mafia while in government. Andreotti's seventh government (1991–92) did take a number of decisive steps against Cosa Nostra - thanks to the presence of Anti-Mafia judge Giovanni Falcone at the Ministry of Justice. "When he says that he took extremely harsh measures against the Mafia, he isn't lying," according to Eugenio Scalfari, the editor of the Rome newspaper La Repubblica. "I think at a certain point in the late Eighties he realised that the Mafia could not be controlled. He awoke from his perennial distraction... and the Mafia, which realised that it could no longer count on his protection or tolerance, assassinated his man in Sicily."[4] His man in Palermo was Salvo Lima who was murdered by the Mafia in March 1992. The murder of Lima meant a turning point in the relations between the Mafia and its reference points in politics. The Mafia felt betrayed by Lima and Andreotti. In their opinion they had failed to block the confirmation of the sentence of the Maxi Trial of 1986 - which had sent scores of Mafiosi to jail - by the Court of Cassation (court of final appeal) in January 1992.

Recent activities

As of 2005, he regularly writes articles for Corriere della Sera. He also recorded a TV spot for 3 mobile company, which began airing in November 2005.

After the April 2006 general election, Andreotti, aged 87, accepted to be the candidate for the Presidency of the Senate for Silvio Berlusconi's House of Freedoms alliance that was still governing at the time. He was opposed by The Union's Franco Marini and lost to him 156 votes to 165.

On 21 January 2008, he abstained from a vote in the Senate concerning Minister Massimo D'Alema's report on foreign politics. This choice, together with the abstentions of another life senator, Sergio Pininfarina, and of two communist senators, caused the government to lose the vote: as a consequence, Prime Minister Romano Prodi resigned. On previous occasions, Andreotti had always supported Prodi's government with his vote. Given his close ties to the high ranks of the Catholic Church, the abstention of Andreotti was read by many as a sort of warning delivered by the Conferenza Episcopale Italiana to the government which at that time was pushing ahead a proposal for legal recognition of unmarried couples, including same-sex couples.

Quotes

By Andreotti

- In response to opposition politician Giancarlo Pajetta, who had claimed that "power wears out" (Il potere logora), Andreotti responded "Power wears out those who don't have it" (Il potere logora chi non ce l'ha). The sentence became proverbial and is widely recognized in Italy.[4][5][6]

- "Power is a disease one has no desire to be cured of."[4]

- On Gladio: "Gladio had been necessary during the days of the Cold War but, in view of the collapse of the East Block, Italy would suggest to NATO that the organization was no longer necessary."

- "You sin in thinking bad about people; but, often, you guess right" (A pensar male si fa peccato, ma spesso ci si azzecca).

- "Never over-dramatise things, everything can be fixed; keep a certain detachment from everything; the important things in life are very few"

- "I recognize my limits but when I look around I realise I am not living exactly in a world of giants."[7]

- "We learn from the Gospel that when they asked Jesus what the truth was, he did not reply." Il divo (film)

- "You always find the culprit in crime novels but not always in real life" Il divo (film)

- "Aside from the Punic Wars, which I was too young for, I have been blamed for everything."[4]

About Andreotti

- "He seemed to have a positive aversion to principle, even a conviction that a man of principle was doomed to be a figure of fun." Margaret Thatcher.[4]

Popular culture

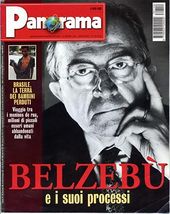

- In Italy, he is often nicknamed Belzebù (Beelzebub) or "The Prince of Darkness" because of his alleged Mafia links, by his detractors. Other disparaging nicknames include "The Black Pope" and "The Hunchback".[8]

- The fictional character Don Licio Lucchesi from the movie The Godfather Part III, a high-ranking Italian politician with close ties to the mafia, was modeled on Andreotti. Tellingly, before Lucchesi was killed, his killer whispered in to his ear "Power wears out those who don't have it".

- A joke about Andreotti (originally seen in a strip by Stefano Disegni and Massimo Caviglia) had him receiving a phone call from a fellow party member, who pleaded with him to attend judge Giovanni Falcone's funeral. His friend supposedly begged: "The State must give an answer to the Mafia, and you are one of the top authorities in it!". To which Andreotti answered puzzled, "Which one do you mean?"

- The Italian satirical magazine Cuore referred to Andreotti as Giulio "Lavazza", where Lavazza is a leading Italian brand of coffee. This was a hint of an alleged involvement of Andreotti in the assassination of banker and felon Michele Sindona, killed in jail with a poisoned espresso.

- He is the subject of Paolo Sorrentino's Il Divo, winner of the Jury Prize at the 2008 Cannes film festival.[9] Andreotti walked out of the movie and dismissed the film, saying he believes he will in the end be judged "on his record".[10]

- On 2 November 2008, Andreotti appeared on the entertainment program Questa Domenica, broadcast on the Italian television channel Canale 5. During his appearance, he appeared to suffer health difficulties and there was speculation he had suffered a stroke. Andreotti was twice posed a question and simply failed to respond, although his eyes remained open. The director cut to an advertisement break, following which Andreotti reappeared in seemingly better condition. The incident was presented to the viewer as a consequence of technical difficulties. A clip of the moment in question is available on YouTube.[11]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Page at Senate website (Italian).

- ↑ Reports: Italy warned Libya of 1986 US strike, Associated Press Writer, October 30, 2008

- ↑ 'Kiss of honour' between Andreotti and Mafia head never happened, The Independent, Jul 26, 2003

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 All the prime minister's men, by Alexander Stille, The Independent, September 24, 1995

- ↑ Andreotti as a lethal "god" in Sorrentino's new film, Cineuropa, May 23, 2008

- ↑ (Italian) Giulio Andreotti, Wikiquote

- ↑ Giulio Andreotti Quotes

- ↑ Beelzebub spoils Prodi's day, The Times, April 29, 2006

- ↑ Il Divo: the Spectacular Life of Giulio Andreotti, The Times, March 19, 2009

- ↑ Andreotti: why I walked out of my own biopic, The Times, March 17, 2009

- ↑ (Italian)Andreotti si incanta...

External links

- "Les procès Andreotti en Italie" ("The Andreotti trials in Italy") by Philippe Foro, published by University of Toulouse II, Groupe de recherche sur l'histoire immédiate (Study group on contemporary history) (French)

- Il Divo a Paolo Sorrentino Film

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Amintore Fanfani |

Italian Minister of the Interior 1954 |

Succeeded by Mario Scelba |

| Preceded by Antonio Segni |

Italian Minister of Defense 1959–1966 |

Succeeded by Roberto Tremelloni |

| Preceded by Emilio Colombo |

Prime Minister of Italy 1972–1973 |

Succeeded by Mariano Rumor |

| Preceded by Mario Tanassi |

Italian Minister of Defense 1974 |

Succeeded by Arnaldo Forlani |

| Preceded by Aldo Moro |

Prime Minister of Italy 1976–1979 |

Succeeded by Francesco Cossiga |

| Preceded by Francesco Cossiga |

Italian Minister of the Interior 1978 |

Succeeded by Virginio Rognoni |

| Preceded by Emilio Colombo |

Italian Minister of Foreign Affairs 1983–1989 |

Succeeded by Gianni De Michelis |

| Preceded by Ciriaco De Mita |

Prime Minister of Italy 1989–1992 |

Succeeded by Giuliano Amato |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||

.svg.png)